INTRODUCTION

International guidelines recommendations for osteoporosis include resistance exercise as part of an overall treatment (Maeda & Lazaretti-Castro, 2014; Moreira et al., 2014), although there is no clear agreement on how it should be prescribed.

In Mexico, National Centre for Technological Excellence in Health (CENETEC, for its Spanish acronym) clinical guideline and the Mexican official standard for the prevention and control of premenopausal and postmenopausal women (Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-035-SSA2-2012), mention exercise as part of the non-pharmacologic interventions for osteoporosis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. These recommendations include: promote physical fitness to avoid sedentarism; promote exercise programs combining strengthening, flexibility and aerobic training to enhance cardiovascular conditioning and prevent bone mass loss; promote physical exercise such as walking, swimming and cycling; and aerobic exercise starting with slow rhythm and gradual increase, with 20 min - 30 min duration per session 2 - 3 times a week (Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-035-SSA2-2012).

There are several recommendations with heterogeneous information and evidence grades regarding exercise prescription as a treatment for osteoporosis. Nevertheless, until now those clinical guidelines have not been submitted to a rigorous appraisal of their methodology, which is a critical need to identify recommendations with the best evidence. This would guide clinicians to take better decisions regarding clinical treatment interventions (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation [AGREE] Next Steps Consortium, 2009; Guayatt, 2008; Khan, Craig & Wild, 2013).

Procedure to design and develop clinical practice guidelines is well defined by Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II (AGREE-II) assessment (AGREE Next Steps Consortium, 2009). This process requires collaboration of a group of professional clinical experts and needs to include patients and care-givers representation. Clinical guides must be based on a suitable appraisal of evidence through high quality systematic reviews, and recommendations must be linked to the evidence that sustain them. Ordinarily, a period of 1 to 2 years is suggested in the development of clinical guidelines, followed by a period to be reviewed. Financial support and endorsement by governmental agencies is recommended, and this financial support must include promotion and implementation.

The ultimate goal of clinical guides is to improve clinical indicators, and therefore must be audited on its use and monitor how implementations change clinical practice outcomes.

It is important that clinical guidelines be constantly upgraded to ensure the inclusion of new evidence. Appraisal is necessary to ensure methodological quality (International Osteoporosis Foundation [IOF], 2015).

The AGREE-II instrument addresses separate aspects of guidelines quality. It consists of 23 items organized within 6 domains followed by 2 global rating items as overall assessment. Each domain captures a unique dimension of guideline quality. The first domain is called scope and purpose, and is concerned with the overall aim of the guideline, the specific health questions, and the target population. Domain 2, stakeholder involvement, focuses on the extent to which the guideline was developed by the appropriate stakeholders and represents the views of its intended users. Domain 3, rigor of development, relates to the process used to gather and synthesize the evidence, the methods to formulate the recommendations and to update them. Domain 4, clarity of presentation, deals with the language, structure and format of the guideline. Domain 5, applicability, pertains to the likely barriers and facilitators to implementation, strategies to improve uptake, and resource implication of applying the guideline. Domain 6, editorial independence, is concerned with the formulation of recommendation not being unduly biased with competing interests. Finally, overall assessment includes the rating of the overall quality of the guideline and whether the guideline would be recommended for use in practice. Each item is rated on a 7-point scale grading the level of agreement/disagreement (AGREE Next Steps Consortium, 2009).

The aim of this study was to assess methodological quality of clinical guidelines that included exercise as an intervention to treat osteoporosis, to identify the recommendations with the best level of evidence.

METHODS

A systematized review of the literature was performed. Only guides published from January 2010 to November 2014 were selected in order to be considered updated. Language was limited to English and Spanish. Guides without exercise recommendations were excluded.

Search strategy was designed using terms as osteoporosis, guideline, exercise and therapy. Data bases included were: PubMed, PEDro, Ovid, EMBASE and ScienceDirect.

Of the selected guidelines, full-text was retrieved and screened for exercise prescription. Blind assessment was done by 4 reviewers who were considered experts in the field and were previously trained in AGREE-II (AGREE Next Steps Consortium, 2009). With each reviewer assessment, a database was created to calculate a scale domain score that is presented as a percentage, as described by AGREE-II instrument user´s manual. Only guidelines that scored over 4.5 in overall assessment were selected for data extraction. All three guidelines applied Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria for levels of evidence and grade of recommendations. An intra-class correlation coefficient was performed to establish agreement between reviewers, using Epidat 4.1 software.

RESULTS

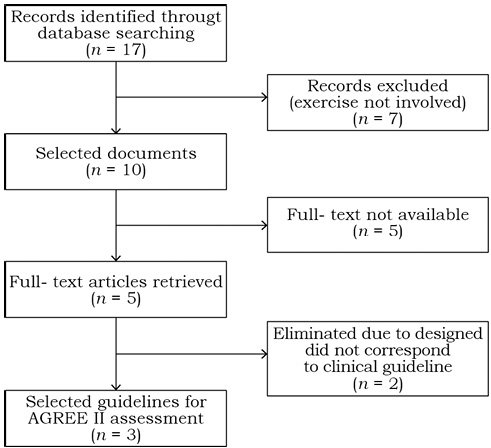

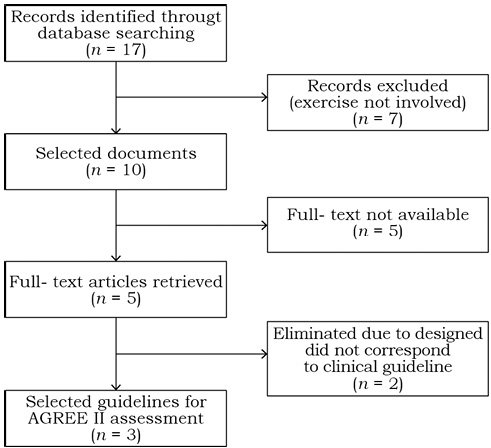

Seventeen documents were identified after inclusion criteria, of which 7 did not involve recommendations on exercise (figure 1). Of the 10 selected documents, full-text was available on 5. After screening, only 3 of these fulfilled the criteria to be assessed by reviewers.

|

| |

|

| |

Figure 1. Flow diagram of CPG selection process.

Source: Author's own elaboration. |

|

Figure 1. Flow diagram of CPG selection process.

Source: Author's own elaboration. Close |

AGREE-II assessment scoring is summarized in table 1. Domain 1 averaged 93.4% (range 84.72-100); domain 2 averaged 58.8% (range 36.11 - 79.6); domain 3 averaged 52.4% (range 18.22 - 79.16); domain 4 averaged 84.2% (range 68.05 - 97.2); domain 5 average 37.5% (range 17.5 - 75); domain 6 averaged 71.52% (range 60.4 - 89.6). Overall guidelines assessment averaged 4.75 (range 3.25 - 6.25). A high agreement between reviewers in overall assessment was observed (intra-class correlation coefficient 0.818, CI 95% 0.368 - 0.994). Recommendation of use without modifications was only suggested for clinical practice guideline 3.

Tabla 1.

AGREE II score.

|

|

Domain

|

CPG1 %

|

CPG2 %

|

CPG3 %

|

|

1

|

84.72

|

94.44

|

100

|

|

2

|

61.11

|

36.11

|

79.16

|

|

3

|

59.89

|

18.22

|

79.16

|

|

4

|

87.5

|

68.05

|

97.22

|

|

5

|

19.79

|

17.70

|

75

|

|

6

|

64.58

|

60.41

|

89.58

|

|

Overall guideline assessment*

|

4.75

|

3.25

|

6.25

|

|

ICCǂ = 0.818 (CIǂǂ 0.368 - 0.994)

|

CPG – Clinical Practice Guideline.

* Average of reviewers overall guideline assessment (scored from 1 - 7)

ǂICC – Intraclass correlation coefficient

ǂǂCI – Confidence interval 95%

Source: CPG1 (Papaioannou et al., 2010), CPG2 (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2014), CPG3 (Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Osteoporosis y Prevención de Fracturas por Fragilidad, 2010).

Abrir

Of the 3 clinical guidelines, 2 scored over 4.5 for data extraction. In order to consider update status, organization, selection of references, recommendations and implementation strategies, table 2 summarizes general characteristics of clinical guides. Description of exercise recommendations to improve quality of life, and other exercise features are detailed in table 3. All recommendations were graded between A and C and evidence levels were based on high quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCT), or RCT with a very low risk of bias, well conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a low risk of bias based on SIGN criteria.

Tabla 2.

Assessed clinical practice guidelines characteristics.

|

|

Characteristics

|

CPG1 %

|

CPG2 %

|

CPG3 %

|

|

Status of the CPG

|

|

New

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Updated

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Organization

|

|

Professional

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Government

|

No

|

No

|

Si

|

|

Searching and selecting references

|

|

Search strategy described

|

Yes

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Total references cited

|

71

|

103

|

153

|

|

Total systematic reviews cited

|

3

|

3

|

11

|

|

Methods of deriving recommendations

|

|

Evidence-linked, formal consensus method

|

No

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Evidence-linked, no description of method

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Consensus method, no detailed description

|

No

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Implementation strategies described

|

|

Year of publication of the previous version of the CPG

|

2002

|

2008

|

2007

|

|

Next update of the CPG

|

2010

|

2014

|

2010

|

CPG – Clinical Practice Guideline.

Source: CPG1 (Papaioannou et al., 2010), CPG2 (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2014), CPG3 (Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Osteoporosis y Prevención de Fracturas por Fragilidad, 2010).

Abrir

Tabla 3.

Summary of recommendations of CPGǂ.

|

|

Recommendation

|

Description

|

Grade

|

Level*

|

Clinical guide

|

|

Exercise to improve quality of life

|

Exercise involving resistance program consistent with age, functional capacity and aerobic resistance to prevent or diminish osteoporosis risk.

|

B

|

1+

|

Moayyeri, A. (2008). The association between physical activity and osteoporotic fractures: a review of the evidence and implications for future research. Ann Epidemiol, 18(11), 827-835.

|

|

Patients with previous vertebral fracture should receive exercise to improve core stability and compensate postural alterations.

|

B

|

1+

|

Moayyeri, A. (2008). The association between physical activity and osteoporotic fractures: a review of the evidence and implications for future research. Ann Epidemiol, 18(11), 827-835.

|

|

Patients with high fall risk should consider exercise to enhance balance and gait training.

|

A

|

1+

|

Gillespie et al. (2009). Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 15(2), CD007146.

|

|

Physical exercise

|

Regular practice is suggested to enhance muscle strength, resistance and balance. Exercise must be individualized to general health of the patient.

|

A

|

1++

|

Grupo de trabajo de menopausia y posmenopausia (2004). Barcelona: Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia. Cochrane Iberoamericano.

|

|

A program that focuses on muscle strength, balance and physical activity (walking) will reduce risk of falls

|

A

|

1++

|

Clinical practice guideline of the assessment and prevention of falls in older people (2004). London. National Collaborating Centre for Nursing and Supportive Care (UK). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance(NICE).

|

|

Physical exercise alone on group or individual prescription is not effective for fall prevention. It is an effective intervention when prescribed as a part of a comprehensive program

|

A

|

1++

|

Clinical practice guideline of the assessment and prevention of falls in older people (2004) London. National Collaborating Centre for Nursing and Supportive Care (UK). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance (NICE).

|

|

Other exercises

|

There is enough evidence to support the recommendation of Tai Chi for prevention of falls on elderly patients, when practiced for more than 4 months.

|

C

|

1+

|

Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (2005). Prevention of falls and falls injuries in the older adult. (Revised) Toronto, ON (Canada).

|

CPG – Clinical Practice Guideline.

* Niveles de evidencia según los criterios grading system (SIGN): www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/50/annexoldb.html

Source: (Grupo de trabajo de menopausia y posmenopausia, 2004; Papaioannou et al., 2010).

Abrir

DISCUSSION

Increase in life expectancy in the last decades is related to changes of morbidity in the elderly population. A clear example of this is osteoporosis incidence increase, that can be linked to sarcopenia and act synergistically in detrimental to bone health (Nikander et al., 2010). Despite this fact should be considered by health caregivers, search results suggest there is lack of current guidelines on this topic, and have been created for developed countries.

Of the assessed guides, domains displayed heterogeneous results. Although scope and purpose (overall aim of the guide, target population and specific health question) are adequately identified in the selected guides, little is described on exercise considerations according to specific population needs (e.g. cardiovascular alterations). Stakeholder involvement denotes a lack integration of multidisciplinary teams of guide developers, none of the assessed guides included rehabilitation specialists, and requirements considered by users (patients and caregivers) have insufficient information. Rigor of development that can denote implemented methodology requires great attention due to its low quality. Synthesis of evidence lacks of important issues to be considered for exercise prescription. Clarity of presentation shows that language, structure and format of the guideline were adequately considered. Applicability requires a greater planning for implementation, lacks of ecological validity because guides are designed for specific country population, and none state resources that will be used for implementation and audit process. Regarding editorial independence, only one guide stated considerations of competing interests. Although two guidelines scored over 4.5 on overall assessment, of these one was considered to have a poor methodological quality (clinical practice guideline 1), and the other was the only one recommended by all authors for its application without changes (clinical practice guideline 3).

Treatment of osteoporosis must consider not only the pharmacologic approach, but non-pharmacologic interventions to obtain the best possible outcome (Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Osteoporosis y Prevención de Fracturas por Fragilidad, 2010).

There is no doubt that exercise is one of the most important recommendations in rehabilitation treatment. Exercise has shown a positive effect on bone mineral density in mayor axial load sites, increasing from 1% to 2% at spine and femoral neck (Bassey, 2001; Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre osteoporosis y prevención de fracturas por fragilidad, 2010; Nikander et al., 2010). Evidence has shown that resistance training programs of moderate intensity that include 3 to 4 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions of each exercise, two to three times a week, may maintain or increase hip and femur bone mineral density (BMD) in postmenopausal women (Giangregorio et al., 2015; Papaioannou et al., 2010). Exercise prescription must improve by specifying the type, duration, intensity and frequency that are not established on recommendations of the assessed clinical guides, possibly due to the professional profile of the developers.

It is suggested to consider individual conditions of patients regarding exercise. When prescription is done in patients with osteoporotic spine fractures, recommendations should include postural alignment, due to associated risk of hyperkyphosis. One of the first symptoms of osteoporosis is loss of height, due to an elevated incidence of vertebral body fractures. Only approximate one third of thoracic deformities associated to vertebral fractures through X-rays images will benefit from medical attention; and less than 10% will require hospitalization (Cummings & Melton, 2002). A vertebral fracture causes spine deformity, increasing thoracic kyphosis (Kanis et al., 2002). When an acute fracture ocurrs, a pain reflex is induced and is associated to an imbalance of flexor/extensor muscles of the trunk. This over demand of flexor muscles increases trunk flexion, and if not treated will cause bone consolidation with structural alterations and hyperkyphosis. Evidence of exercise programs preventing these deformities has been stated by diverse clinical researchers (Bonner, Sinaki & Grabois, 2003; Huntoon, Schmidt & Sinaki, 2008; Sinaki, 2010). Therefore, these exercise programs should be detailed on clinical practice guidelines (Forriol, 2001; Hsu, Chen, Tsauo & Yang, 2014; Riggs, Khosla & Melton, 2012; Wong & McGirt, 2013).

Other benefits from exercise programs regarding postural correction and balance training is fall risk reduction, which is directly related to incidence of fractures. This is accomplished by proprioceptive, flexibility and strength training (Li et al., 2005; Sinaki, 2012; Wayne et al., 2012).

Cardiovascular pathologies must be considered when prescribing exercise in these patients, due to common risk factors and mechanisms involved in the regulation of bone and cardiovascular metabolism (Farhat & Cauley, 2008; Szulc, 2012; Wayne et al., 2012).

The benefits of exercise on osteoporosis require a more profound consideration. Much has been written, but the lack of conclusions of this intervention on osteoporosis is notorious. Benefits of exercise include its positive influence on bone strength (lack of evidence to treat, but adequate to prevent) and risk of falls. Other conditions that might improve with exercise are general health, diabetes, cardio and cerebral-vascular diseases, urinary incontinence, cognitive decline, psychological conditions. However, attending physicians refer to exercise recommendations in an unspecific way (eg. suggesting walking, swimming, stretching) (Russo, 2009).

Principles of bone adaptation to exercise have been described by different authors (Borer, 2005; Lanyon, 1987; Turner, 1998). Principles of exercise prescription should be considered:

• Overload: Bone stimulus must be greater than the usual load.

• Individual differences: Genetics determines the grade of bone adaptation. Individual with lower bone mineral density will achieve greater benefits from osteogenic loading.

• Reversibility: If bone stimulus is suspended, the benefits achieved are lost.

• Specificity: Bone response to exercise loading is site specific.

Current available evidence has allowed the elaboration of exercise prescription proposals to prevent and maintain bone health, preventing associated fractures (table 4). In a clinical context, it has not been possible to establish the osteogenic response to exercise, due to the limitations of screening methods to assess the structural changes that participate on bone strength besides bone mineral content.

Tabla 4.

Evidence based proposal of exercise influence on bone.

|

|

Subjects

|

Exercise type

|

Duration and frequency

|

Femoral neck

|

Lumbar Spine

|

Other outcomes

|

|

Pre-menarche

|

High impact

|

20 - 20 min/days

3.3 days/week

|

↑ BMD*

|

↑ BMD

|

|

|

Adolescents

|

Scholar Sports activities (with weight bearing)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pre-menopause women

|

High impact

|

< 30 min/days

4.6 days/week

|

↑ BMD**

|

|

|

|

Impact with

high magnitude

|

1 h/days

3 days/week

|

↑ BMD

|

↑ BMD

|

|

|

Post-menopause women

|

Impact with high magnitude

|

2 s/days

3 days/week

|

↑ BMD

|

↑ BMD

|

|

|

Fortalecimiento de extensores de tronco

|

10 times/days

5 days/week

|

|

|

Lower incidence of vertebral fractures

|

|

Elderly women

|

Balance

|

High dose

≥ 2 h/week

|

|

|

Lower incidence

of falls

|

* BMC = Bone Mineral Content; **BMD = Bone Mineral Density

Source: Iwamoto (2013).

Abrir